Over the centuries, the significance of the Dorje Phagmo has grown through a process of ritualization that increased the distance between the people who worshipped her and the women who embodied her (for a detailed analysis of the process see Diemberger 2007. The following paragraphs are quoted from chapter 7).

Every girl who was recognized as the reincarnation of the Samding Dorje Phagmo went through a complex process managed by Samding monastery and religious authorities such as the Dalai Lama. The process of identification and training merged individual experience with the features of the deity and the memory of its previous historical incarnations. Some of the women came to embody the sacred persona in such a way that their individual identity almost disappeared as a simple name in the lineage, while others became significant personalities and scholars of their time over and above the sacredness attributed to them by their “office.” The Ninth Dorje Phagmo, for example, became a renowned spiritual master not only for Samding but also for the Nyingma tradition, discovered some terma, and died at Samye. Her skull is still preserved and worshipped as a holy relic in the Nyingmapa monastery on the island of Yumbudo in Yamdrog Lake. The current Dorje Phagmo has survived and maintained the tradition in a socialist context, adapting to the varied ways political and social practices have transformed and shaped contemporary Tibet during her lifetime.

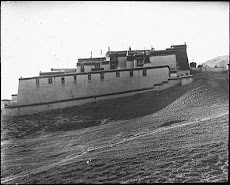

The Twelfth Samding Dorje Phagmo, who is currently the head of Samding monastery, underwent the same process of identification as her predecessors, but her life experience has been unusually eventful. Born in 1938 in Nyemo, she has lived through the most dramatic events of modern Tibetan history, including the Chinese annexation of Tibet in 1951, the uprising in 1959, the Cultural Revolution, and the post-Mao era. As a religious leader she experienced both the extreme hardship of class struggle and the subtle ways prominent members of her class were co-opted as part of the modern political elite. She was included in the Chinese administration’s effort to integrate preexisting political and religious leaders of minority nationalities, a strategy that is usually defined as the United Front policy and takes its name from the organ of the Communist Party that has the specific task of dealing with the noncommunist elements of society. The Samding Dorje Phagmo was appointed to various positions in the Chinese People’s Political Consulting Conference (CPPCC) at both the regional and national levels in the 1950s and early 1960s, and again in the post-Mao era. In 1984 she became the vice president of the People’s Congress of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR); she was reconfirmed in this position in January 2003.

The Dorje Phagmo, as an institution, was transformed over the centuries to merge with the prevailing social and political climate, while retaining its distinctive spiritual tradition and the reincarnation lineage. The institution established with the death of the Gungthang princess was thus integrated in different political and religious frameworks: Bodongpa, Karmapa, Gelugpa, the Qing empire, and eventually the PRC. The last step was a huge leap and involved the transition from a Buddhist religious and political culture to a radically secular ideology: Chinese Communism. However, there are some surprising continuities with premodern political practices, for the United Front policy followed strategies that, in practice, had certain similarities with those of the Qing empire. Implemented by the Communist Party since its early days in order to secure control over Tibetan and Mongolian areas, the policy often required a process of negotiation with the local traditional leadership. This approach was important particularly in the 1950s and after Mao and tried to harness, strategically, the moral authority of the past within the modernist project of communist China. It is therefore possible to detect some remarkable continuities between premodern and modern Tibet, across the conventional divide between “old society” (spyi tshogs rnying pa) and “new society” (spyi tshogs gsar pa).